by Gina Fegan

* Article Wired Magazine, Jan 2012, by Jason Tanz

(www.wired.com/magazine/2011/12/ff_cowclicker/all/1)

My issue with all of these words is that they are more about the buzz and media hype that they generate than a real understanding of what is actually going on and where it will lead us.

As Marshall McLuhan put it so succinctly “anyone who tries to make a distinction between education and entertainment doesn’t know the first thing about either”. From painful experience gained, I wholeheartedly agree with McLuhan. Taking this a little further and unpacking this statement it reveals two profound truths:

1. All entertainment teaches us something – even if we don’t know what it is at the time.

2. The more we are ‘entertained’ or engaged the quicker we learn.

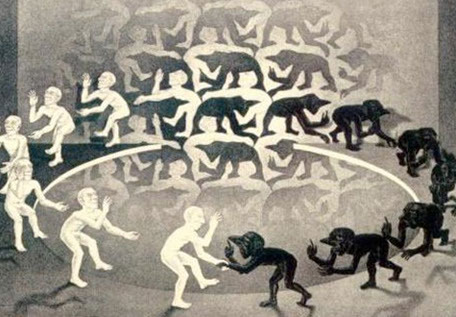

It only takes cursory reflection to come to the conclusion that we know this already; it is not new, its just being articulated differently. Chess teaches the philosophy of war. All children’s playground games serve a purpose, ranging from enhanced physical dexterity to the niceties of social interaction. Stories use our engagement with the characters to tell us how to behave, or how to react to challenging circumstances, which we may confront in life. Being chased by zombies may appear a frivolous use of time, or may enhance physical dexterity useful in keyhole surgery whilst at the same time exemplifying the benefits of evasive action when in the presence of superior odds.

The question is, do we know what skills we are acquiring and why, or when, they might be useful.

Having accepted the value of entertainment in learning, (studies of which have been referred to as Ludic Epistemology; Ludic Learning; Learning to Play Playing to Learn), the next trick is to master it.

From my experience in teaching a foreign language the tools of the trade include:

– engaging the students,

– using all their senses,

– providing a safe place to take risks,

– giving real time feedback through positive criticism.

Some of the activities that do this really successfully are classic games, but equally useful are group discussions, reading, writing, singing, and sharing experiences, all designed and facilitated by the ‘animator’ or teacher. So the whole experience is more that the single game and needs a broader understanding, and a greater context within which to place the particular task.

So pulling back we can see that ‘gamification’ is a process of using something entertaining to engage someone, combined with positive feedback to cause behavioural modification. This does not make it an end in itself, a singular act; in fact it shows that it is one of the many tools in the game we sometimes call life.

Gina Fegan