Health care is a solemn business and understandably so. For those in mobile health this has important implications: you don’t want an app for cancer sufferers, say, to be anything other than serious and straightforward for risk of trivialising what is an incredibly important issue.

The gamification of mobile health (or gHealth), then, might seem to be a difficult sell. A recent article in HealthBiz Decoded may claim that gamification is “sweeping the healthcare app world” but one of the leading examples it cites – the SuperBetter app – describes itself on the App Store as “not a game”. Instead, it is “an awesome tool created by game designers who take the best of games and apply it to your real life so you can get stronger, happier, and healthier”.

Which sounds quite a lot like a game.

Partly this is a problem of definition, with app designers keen to avoid the word “game” as they go after an adult audience for fear of its (unjustly) juvenile connotations. Is Mango Health, an IOS app that “makes it fun and easy to manage your medications”, including points and rewards, a game? Maybe. But it doesn’t define itself as such.

This might sound like splitting hairs. But definitions are important and there will be many adults who will be put off by the idea of playing a computer game to help improve their health. They will see it as trivial and irrelevant. And that could be problematic.

For children on the other hand gaming is far from a dirty word – quite the opposite, in fact. And this means that gamification of mobile health services for sick children is a lot more straightforward – and arguably advanced – than for the adult market.

Anna Sort is founder and CEO of health ramification start up PlayBenefit and works as as a gamification consultant in the healthcare sector. She tells MobileHealthGlobal that the key to communicating with children about disease is that “the child… understands the disease, how it works, what the risks are and how does his / her treatment work, as well as other aspects such as diet and exercise”.

This is where gamification comes in: children need to know about their disease in order to help fight it, but the medical terms we use as adults can prove scary and counterproductive.

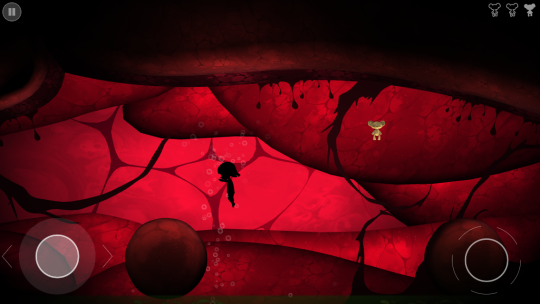

Sort cites Nightmare: Malaria, an iOS and Android app that teaches teenagers about malaria, is an example of how gamification can help to educate young people about disease. The game sees players dropped into the bloodstream of a young girl infected with malaria, from where they must escape using mosquito nets to avoid the killer mosquitos. The message here, hammered home in an amusing, engaging way, is that the risk of malaria can be reduced by using nets.

Monster Manor, an iOS and Android app from Ayogo Health, extends this methodology, using gaming to encourage children with Type 1 Diabetes to manage their blood sugar “by adding a dose of fun to the challenge”.

Ayogo CEO and founder Michael Fergusson tells MobileHealthGlobal that his company wants to “connect with the patient on an emotional level, and influence their decision making from that point”. In Monster Manor, this means that gamers are rewarded with additional gameplay every time they log their blood sugar information. There is a wider benefit too, with these logged blood sugar levels easily read by parents and doctors.

Monster Manor has already found support among the medical profession, being shortlisted for The Diabetes Times’ award for Value and Improvement in Medical Technology in 2013.

Simon O’Neill, director of health intelligence and professional liaison at Diabetes UK, believes the Monster Manor method can bear serious dividend. “Parents tell us that their children often find regular blood glucose monitoring very hard to accept and it can often become a source of tension in families,” he says.

“By turning the testing into a game we hope it will encourage young children with diabetes to manage their condition more effectively and help them succeed in achieving tighter blood glucose control in their early years. In turn, this would help them reduce the risk of developing the serious complications associated with diabetes in later life.”

gHealth, as these examples show, can be used both to educate and to encourage better behaviour among patients. Professor Kevin Werbach, author of For the Win: How Game Thinking Can Revolutionize Your Business, believes the latter may be its key role.

“Gamification is fundamentally a tool for motivation,” he tells HealthBiz Decoded. “In healthcare, it’s primarily useful for behaviour change – helping people commit to and stick with activities they know they want to do.”

Werbach says that gamification can help people with anything from doing more exercise to taking medication regularly. Or, as we have seen above, helping children to remember to log their blood sugar levels or to use mosquito nets.

And yet we may have only scratched the surface of gHealth. PlayBenefit says that gamification can be used within the health sector for anything from rehabilitation to eLearning for healthcare professionals. And as the number of tablets, and smartphones around the world continues to expand at a healthy clip, we can expect the number of gamified health apps to expand with them.

Could we see doctors some day prescribing games to help with our ailments?

Who knows. There may be resistance now among adults but the attitudinal shift that will come as as generations raised on video games grow up and succumb to the inevitable problems of ageing could change all that.

And that might be for the good of everyone.

@play_benefit