One of the most difficult things about being ill is trying to get to the doctor. You know you should, of course, but your head hurts, you’re freezing cold and the idea of getting on public transport makes your stomach churn.

That is why doctors traditionally make home visits, coming to see the patient rather than forcing the patient to come and see them. The problem, at least in the UK, is these visits are becoming increasingly rare: in 2010 the Daily Mail – not the most sympathetic paper, admittedly – claimed that doctors are agreeing to just one in 50 requests for out-of-hours home visits in some parts of the country.

And you can understand why: in the time it takes for a doctor to see one person at their house, they could have seen between two and four patients at the surgery. In the time of stretched NHS resources, that kind of equation just doesn’t add up.

In the US, meanwhile, there were just 4,000 doctors who made home visits in 2010, which isn’t going to make much impact in a country of 319m people.

Could Uber be the answer to these problems?

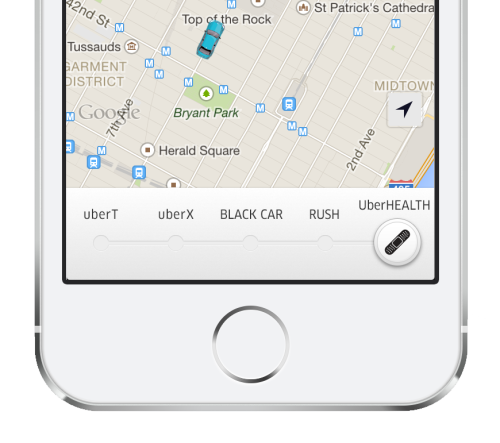

The obvious response would be: no of course not, it’s a taxi company (of sorts). But Uber itself has other ideas. In October 2014 it launched UberHEALTH in Boston, New York and Washington DC, allowing Uber users to order a flu prevention pack delivered to their home or office, with the added option of requesting a nurser to administer a flu vaccine shot at a place of their choosing.

The experiment was limited to just one day, October 23, and nurses vaccinated 2,057 people in total. Uber described the exercise as “a proof of concept” in a report published last week in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

“We believe that the results show that such an effort is feasible because of the availability of new information technology and the new organisations that the technology makes possible,” the report adds.

Uber claims that the test proved there were a significant number of people who wanted to vaccinated against flu but were put off by the inconveniences of travel and cost. In a survey given to those vaccinated, 78.2% of respondents said that the delivery of the vaccine was very important in their decision to be vaccinated, while 15.6% said it was moderately important.

By all standards, then, the test was a success. And it was no surprise that Uber repeated the experiment last week on a wider scale, this time to 36 US cities, with the company telling the Boston Globe that it expected to deliver 10,000 vaccines.

And Uber isn’t stopping there. At the start of November healthcare communications specialistVoalte announced that it was working with Uber and Sarasota Memorial Health Care System to create an app that would make arranging transport easier for people who need a ride to their doctors’ appointment.

“This innovative initiative with Voalte and Sarasota Memorial Health Care System is a great example of how communities can leverage Uber’s local infrastructure and logistics to help improve the lives of those in need,” Matthew Gore, general manager of Uber Florida, said at the time.

Four days later, Uber announced it was partnering with health app Practo, allowing consumers in India, Singapore, the Philippines and Indonesia who book a doctor’s appointment on Practo’s apps to see the closest Uber available.

Even more significantly, Uber last week named John Brownstein, director of Computational Epidemiology Group at Boston Children’s Hospital, as its first health care advisor. “With his guidance and expertise, we will be able to identify other ways we can leverage the Uber platform so we can drive to a healthier future,” Uber explained on its blog.

Brownstein has big plans for Uber in health care. He told Buzzfeed that Uber’s drivers, who now number around 400,000 in the US alone, could one day transport patients to doctor’s offices, particularly for scheduled visits.

“We know that people don’t follow up on treatments on whatever course of therapy they’re on,” he said. “That can ultimately lead to poor health but also a huge amount of costs to the health care system. Any way to create more convenience and more options for people to access health care means the overall cost of the health care system is going to come down.” As an example of this, he mentioned ambulance rides, which can cost thousands of dollars and are often unnecessary.

Uber, of course, is not a charity and the fact that US health care costs hit $3 trillion in 2012 are unlikely to have passed it by. Being linked with health care could also give a useful PR boost to a company that has had more than its fair share of controversies over the last few years.

Uber’s plans for health are not without their doubters, though. For a simple, scheduled trip to the doctor a Uber might be just the thing. But using it to replace an ambulance could be risky in other circumstances. Of course, no one would think of calling an Uber if their partner collapsed with a heart attack. But Uber’s excursions into this territory could leave a significant grey area.

Dr. Elizabeth Anderson, an internal medicine doctor in Fairfax, Virginia, who spoke to Buzzfeed, also raised the question of doctor patient relations. These, she explained, are crucial in reducing medical errors and should not be sacrificed for the convenience of a flu shot in your home.

“As a society,” she added, “what has happened is that we put expediency and immediacy above other more valuable qualities with regards to health care and we’re paying for that.”

She undeniably has a point. And yet with Uber working hard to expand its services into areas such as food (UberFRESH), postal deliveries (Uber Rush) and even boats (UberBOAT in Istanbul), further expansion into healthcare looks inevitable. On balance, that is probably a positive thing, a demonstration of how Uber can use its ubiquity for good.

“Uber is a lot more than a transportation app,” says Uber’s Gore. “It is a platform that is meant to be utilised to help address local industry and community challenges.”